Monsters

From portents of divine messages and wonders of nature, monsters were transformed into proofs of developmental laws.

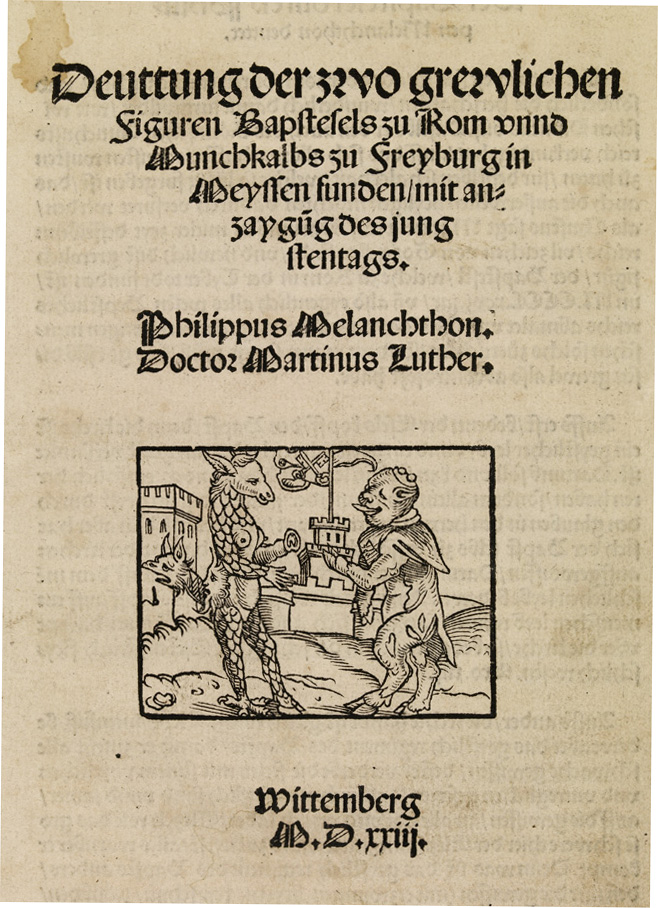

Before the eighteenth century, ‘monsters’—malformed, often aborted or still-born animals and (occasionally) children—were seen as wondrous singularities of nature. In the contemporary culture of spectacle, they were displayed in ‘cabinets of curiosities’. Monsters also carried divine messages. In the 1400s they signified God’s anger at such vices as sodomy or pride; in the politically and religiously charged atmosphere of the Reformation and the English Civil War they portended heresy. Only with the end of the religious wars in the late 1600s did naturalistic causes gain prominence. These included excess of seed and the maternal imagination: the belief that a woman’s thoughts affect the form of the child.

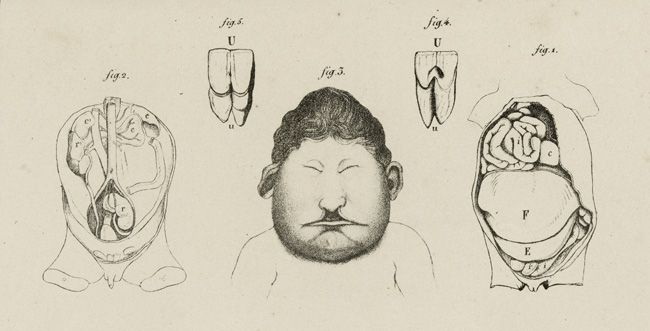

By the late 1600s, monsters became a key bone of contention in debates over generation. They particularly troubled advocates of pre-existence, for why would God have created such germs? Grouping monsters together eventually made clear that, far from singular, they conformed to certain regular laws. Supporters of epigenesis argued that monsters were outcomes of an excessive or deficient developmental force. Studying the timing and nature of obstructive events pointed towards crucial moments in the formation of an embryo. No longer wonders, monsters could now teach about normal development.

The political monster, 1523 |

Monsters as proofs of developmental laws, 1791 |