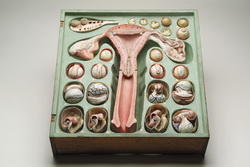

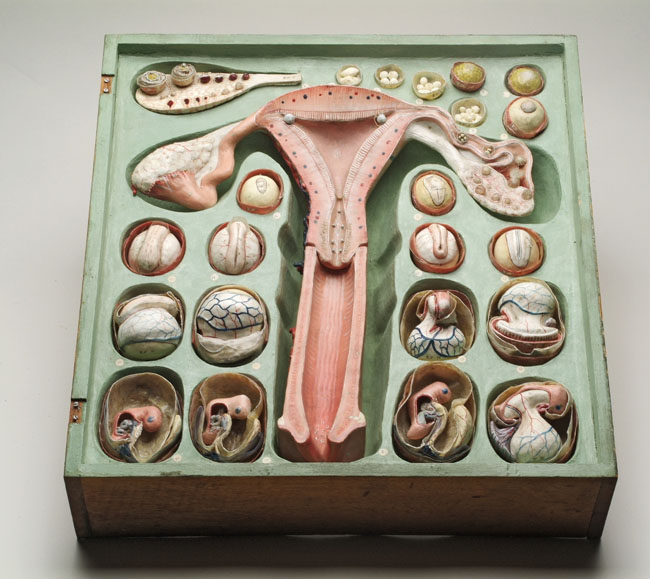

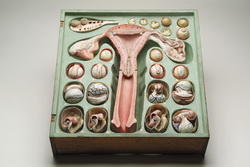

‘Eggology’ in papier mâché.

The now visible egg and other embryological discoveries

attracted model-makers’ attention. The most commercially successful

was Dr Louis Auzoux, whose factory furnished educational institutions

and individuals in France and abroad with innovative models

in papier mâché, a material more robust than wax, and so more

suitable for teaching. Many of Auzoux’s models could be taken

apart and put together again. This 21-piece ‘ovologie’ represents

the human female reproductive system and vertebrate embryonic

development from ovulation to the ‘formation of the embryo’.

The earliest known reference to this series comes from the sales

catalogue attached to the textbook, Leçons élémentaires

d’anatomie et de physiologie humaine et comparée (1858,

pp. 350–1), but the pictured set was produced after Auzoux’s

death in 1880.

41 x 43 x 11 cm.

Museum Boerhaave, Leiden.

The mammalian egg. Since

de Graaf, the large follicle in

the ovary was regarded as the egg, but many scholars doubted his results.

They wondered, among other things, how such a big object could pass through

the narrow tubes. In the mid-1820s, Karl Ernst von Baer

was certain that the egg must originate in the ovary but that it was not

the follicle de Graaf had observed. He had his teacher and colleague Karl

Burdach give him a house bitch that had gone into heat a few days earlier.

Seeing only follicles in the ovaries, Von Baer was about to give up, when

with the unaided eye he noticed ‘a yellow spot’ in some of them. Opening

one, he lifted the spot into a watch glass for microscopy. He had hoped

so much for this sight, but when it finally came he recoiled ‘as if struck

by lightning, … afraid I had been deluded by a phantom’. The discovery of

a tiny elementary structure, from which a whole organism developed, was

an important inspiration for the later cell theory.

Cells and disciplines

Microscopy led to the discovery

of cells and embryology was institutionalized in medical courses.

Researchers in German institutes of anatomy and physiology followed

Pander and von Baer. After the discovery of

the true mammalian ovum, a more general cell theory was developed

from the late 1830s. In the early 1850s, Robert Remak, whose Jewish faith

hindered his career at the University of Berlin, argued that all cells arise

from pre-existing cells, from the egg via the germ layers to the tissues.

He also taught that in vertebrates each layer gives rise to particular cell

types, for example, liver from endoderm, muscle from mesoderm and nerve

from ectoderm.

By the 1850s special anatomical courses for medical students were

embryology’s main base. Developmental approaches were very important,

but the science achieved only limited institutional independence. A new,

physics-oriented physiology reckoned embryos intractable with physico-chemical

methods and abandoned the subject to anatomy and the newly independent zoology

institutes. Few human specimens from the first month and none from the first

two weeks were known, but by teaching that vertebrate development follows

a common pattern, comparative embryology licensed the use as surrogates

of frog, chick and domestic mammals.

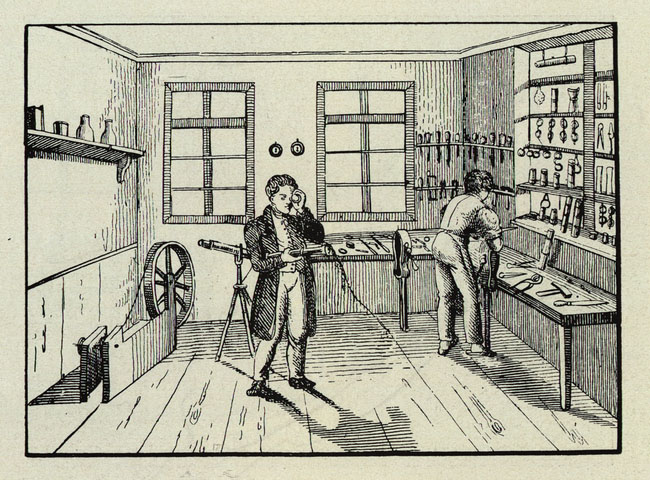

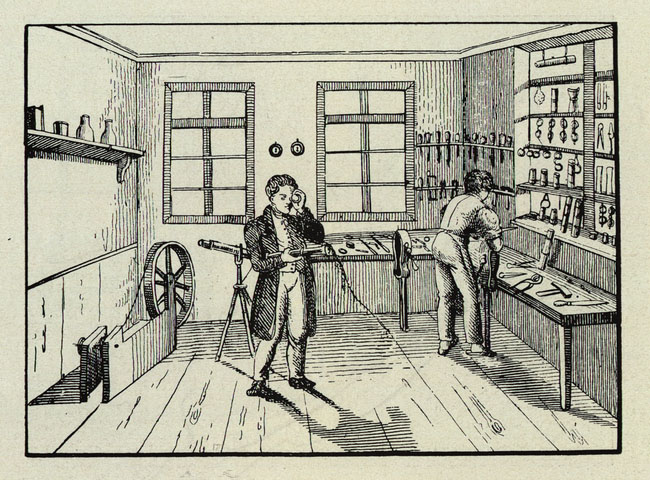

An optician’s workshop. The foundation of the

University of Berlin in 1810 and the expansion of the

medical sciences stimulated the crafts of instrument-makers

and opticians, whose numbers in the Prussian capital

dramatically increased. The microscope was highly sought-after,

especially following the invention of achromatic technology

in the 1830s. While earlier images had been surrounded

by coloured fringes resulting from the refraction of

natural light, now scientists saw vividly and sharply.

The expensive new microscopes were initially purchased

only for the private laboratories of professors and

by wealthy medical students. Later, laboratory training

was extended to every student and cheaper microscopes

became standard equipment for all.

Woodcut titled ‘Mechaniker-Werkstatt’ (1832) from

Franz Maria Feldhaus, Carl Bamberg. Ein Rückblick

auf sein Wirken und auf die Feinmechanik, Berlin:

Askania-Werke, 1929, fig. 13, p. 23. 24 x 17 cm.

Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek,

Göttingen.

An optician’s workshop, 1832

|

|

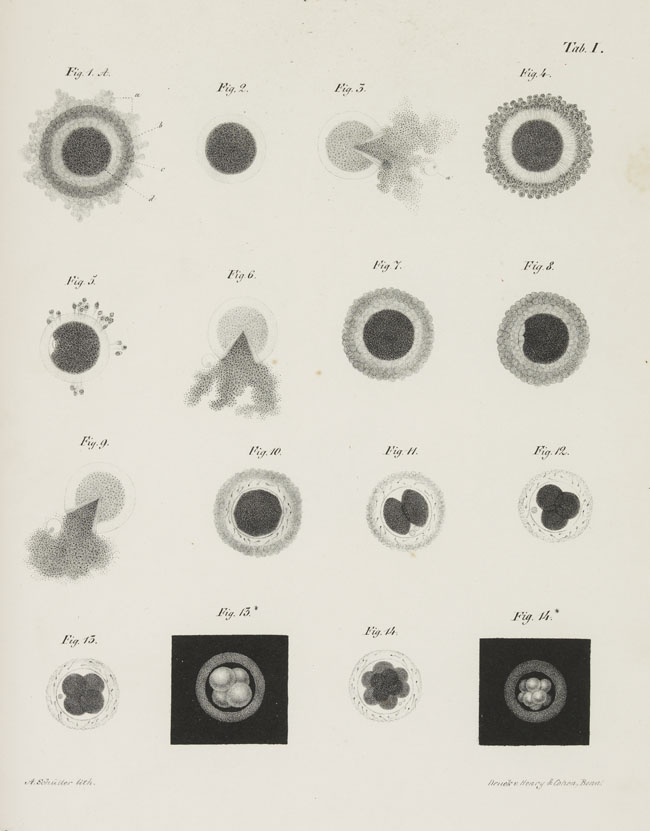

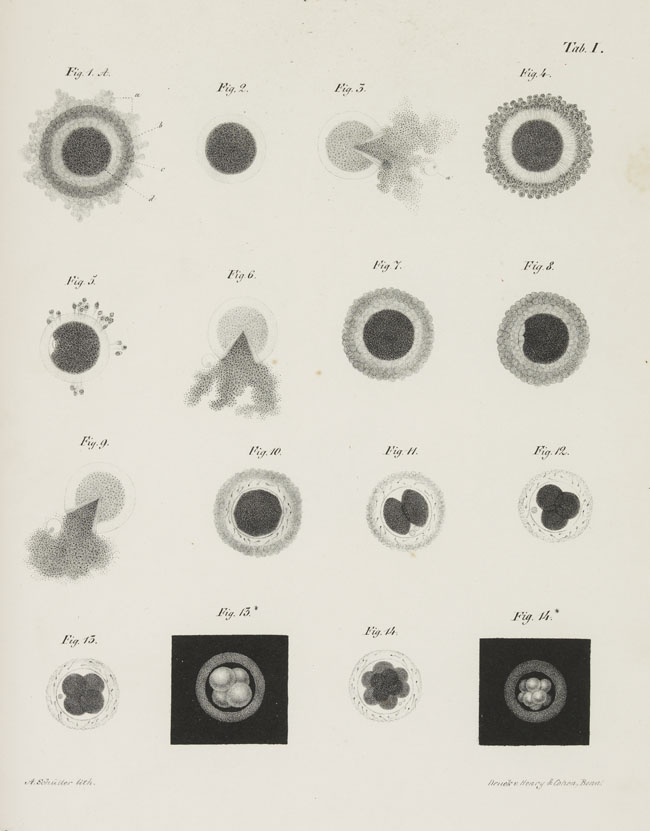

Cleaving dog embryos. Inspired by

von Baer, in the early 1840s

the Giessen anatomist Theodor Bischoff authored pioneering

studies of early mammalian development, first of the

rabbit and then of the dog. Even for these relatively

accessible species, the construction of developmental

series was severely limited by what he could collect

from animals he bred and bought. These lithographs show

cleavage in dog eggs taken from the ovary (figs 1–6)

and the Fallopian tubes (figs 7–14). Three have been

opened with a needle to release the yolk and with it

the ‘germinal vesicle’ (the modern nucleus). Figures

13* and 14* are reversed, white on black, to mimic the

effect of reflected-light microscopy. Bischoff was still

cautious about interpreting cleavage as a process of

cell division, but these and their rabbit counterparts

were soon reproduced as wood-engravings

in textbooks and more popular works, and also as wax

models.

Lithograph by A. Schütter after Bischoff’s drawings,

printed by Henry & Cohen, from Th. Ludw. Wilh. Bischoff,

Entwicklungsgeschichte des Hunde-Eies, Braunschweig:

Friedrich Vieweg und Sohn, 1845, plate I, 27 x 21 cm.

By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University

Library.

Lithograph of cleaving dog embryos, 1845

|