Embryos on show

Schools did not teach embryology, but non-medics had some access in museums and ever cheaper illustrated books.

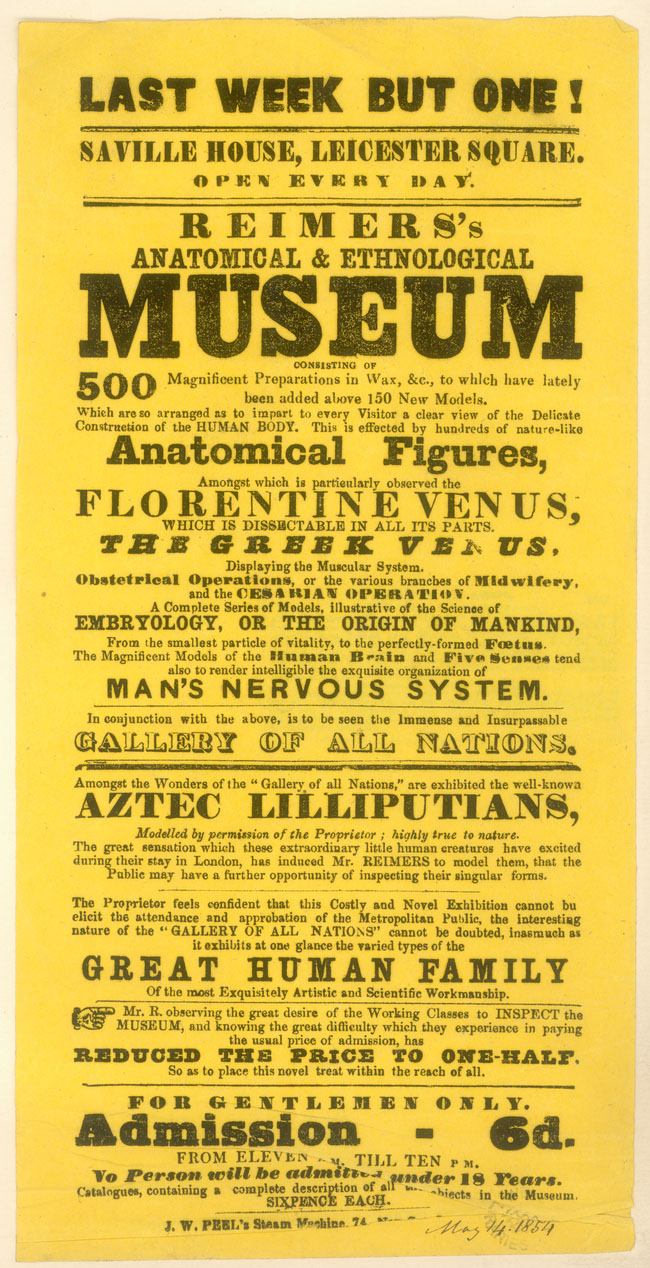

The general public could visit some state collections. For example, in Vienna, the Florentine waxes were open to the public every Saturday from 1822. The mid-1800s also saw the rise of private anatomical museums. Their entrepreneurial owners claimed, democratically, to target ‘the humble artisan’. The admission charge—1 shilling for Joseph Kahn’s London museum—was probably too high, but these were among the few attractions to admit unaccompanied women, if often at different times from men.

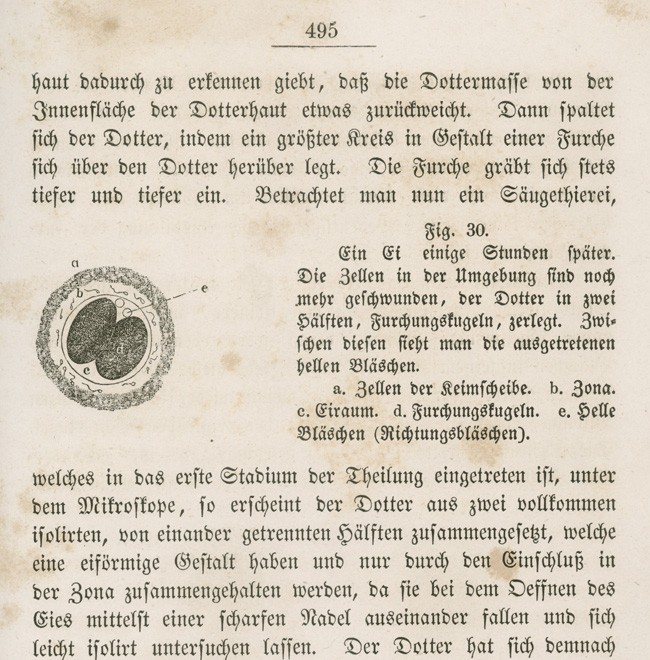

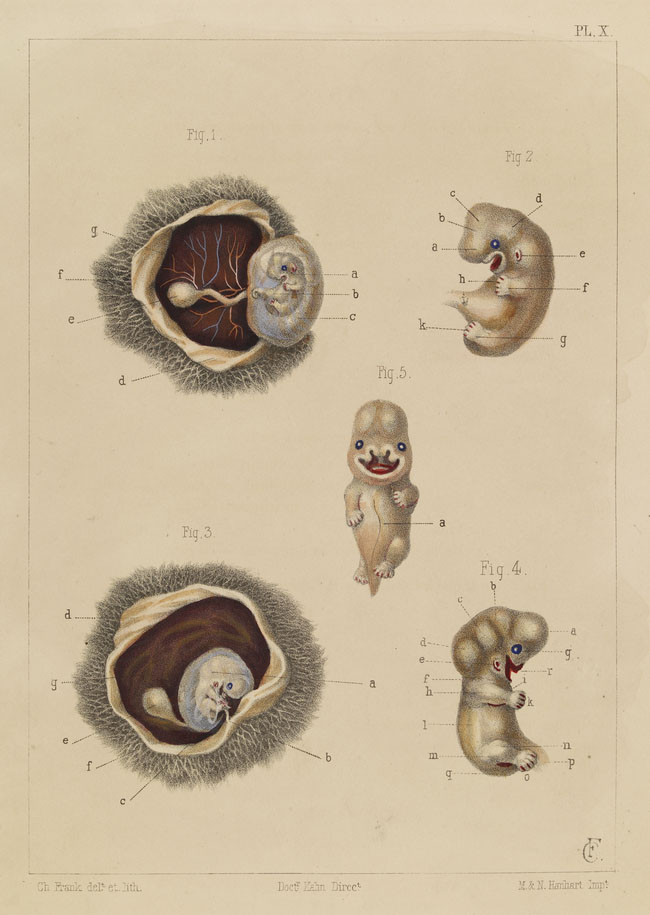

Association with sex limited distribution of pictures and models of embryos. They appeared in the popular museums in the titillating context of naked and dissected bodies and genitals ravaged by venereal disease. Embryology was not as prominent as geology and chemistry in the first great wave of popular science. But interest in human origins was great and wood-engraving made printing cheaper. So even before Darwinism middle-class people did not have too much trouble finding images of development, if they knew where to look.

Handbill for an anatomical museum, 1853 |

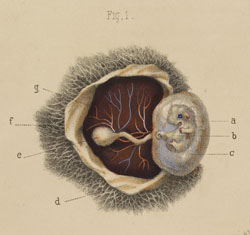

Kahn’s vivid atlas based on models, 1852 |