Seeing the fetal skeleton

In the early to mid-twentieth century, X-rays were widely used to predict a difficult labour.

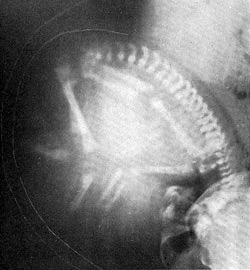

Announced to the world in early 1896, Wilhelm Roentgen’s X-rays were the most sensational invention in what has become the major field of medical imaging. By 1897, obstetricians had X-rayed the female pelvis. They saw fetal parts by the twelfth week of pregnancy and constructed maps of the forming bones. Yet by the mid-twentieth century radiography of fetal development had been largely abandoned. While X-rays were still occasionally used to diagnose dangerous cases of pregnancy outside the uterus, fetal death and abnormalities, obstetricians concentrated on more effective control of labour.

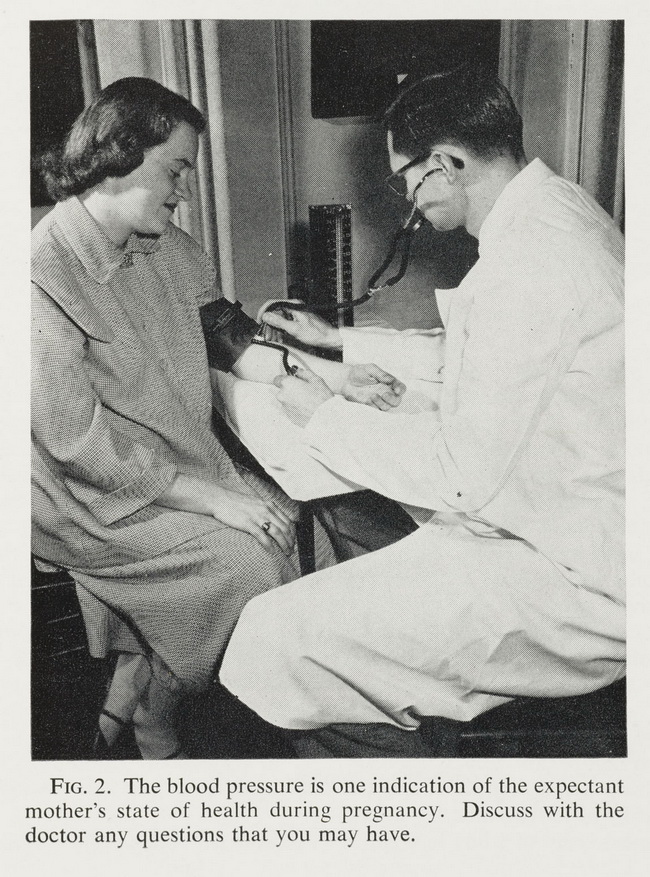

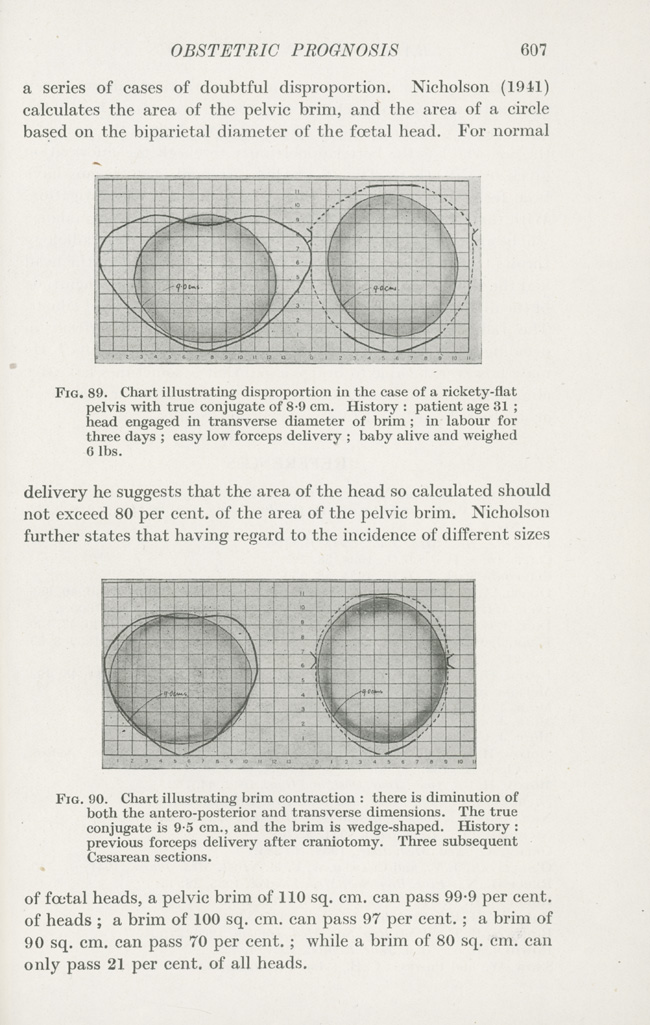

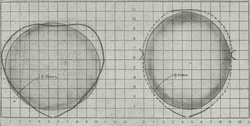

Between the 1920s and 1950s, obstetricians studied the shapes and sizes of pelves, compared them with fetal heads, and predicted fetal presentation and position. Palpation was now supplemented with the supposedly more objective method of tracing, from radiograms, an outline of the pelvic bones and fetal head to estimate whether the head would fit through the pelvis. Yet the use of X-rays was tainted with danger. After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the mutagenic effects came under much closer scrutiny. The final blow was a 1956 study by an Oxford team led by Alice Stewart that found an increased incidence of childhood cancer following in utero irradiation.

Charts of pelvic dimensions and shapes, 1946 |

A textbook of obstetric roentgenology, 1955 |