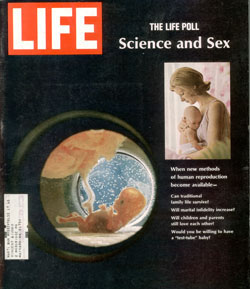

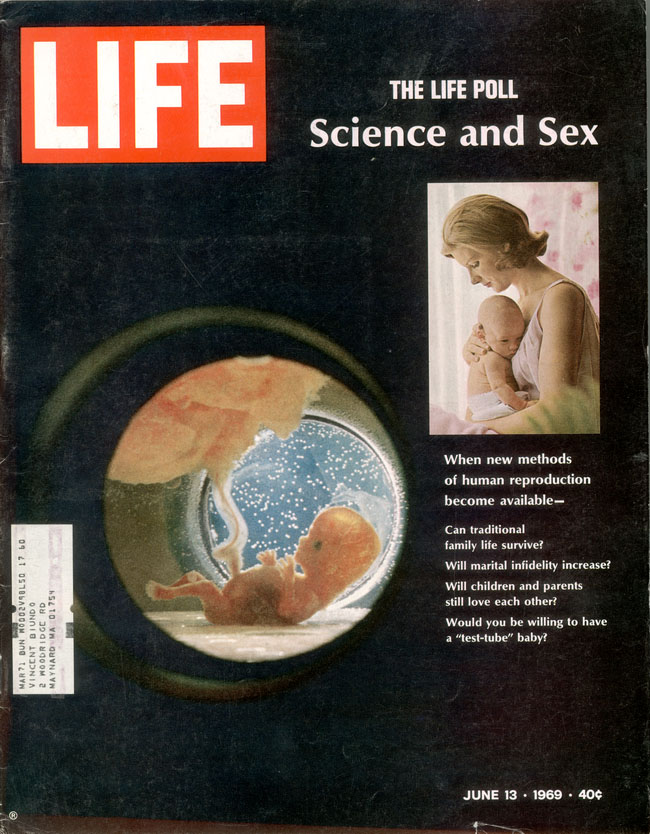

The first ‘test-tube baby’

In vitro fertilization depended on collaboration between physiology and obstetrics and the careful management of publicity.

In the late 1960s, the Cambridge reproductive physiologist Robert Edwards teamed up with the Oldham gynæcologist-obstetrician Patrick Steptoe to capture eggs from ovulating women and fertilize them in vitro. They thus overcame the lack of live human eggs, which had plagued reproduction researchers since Rock and Menkin’s early attempts at Boston’s Free Hospital. Laparoscopy, of which Steptoe was the British pioneer, allowed intervention into the abdominal cavity through just two small holes: one for the camera and one for the surgical instrument. Edwards and Steptoe worked from the first successful in vitro early development (1969) to the first embryo implantation (1976).

But in contrast to the trust in science that had been dominant in the postwar era, many in the 1970s were suspicious and worried. The American bioethicist Leon Kass typically called these interventions a ‘slippery slope’ leading to a Brave New World nightmare, ‘the full laboratory growth of a baby from sperm to term’. Radical feminists feared men controlling reproduction and coercing women into motherhood. The researchers carefully administered the publicity around the birth of the first ‘test-tube’ baby, Louise, to Lesley and John Brown on 25 July 1978. Depictions abounded of reproduction and development in vivo and in vitro.

Robert Edwards and colleagues in their Cambridge laboratory, 1969 |

A publicity photograph of the ‘test-tube’ baby-makers with Louise Brown, 1978 |