A blind spot in anatomical images

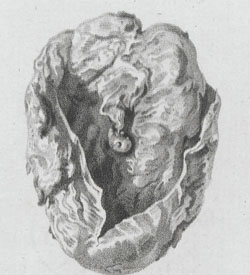

Soemmerring set out to fill in a large gap in pictures of early human development.

Soemmerring drew attention to a remarkable absence when reviewing some plates representing embryos in the late 1780s. None showed ‘a sufficient completeness and such progression of individual stages, that one can recognize almost effortlessly the growth and development of the human body from the third week until the fifth or sixth month’. Older figures were crude and ignorant, he wrote, and most contemporaries’ were little better.

Soemmerring admired Hunter’s ‘almost complete and excellent series of embryos from the fourth month until almost complete maturity’, but was less impressed with the earlier specimens. He initially intended to produce a German edition of the text to Hunter’s atlas, which Hunter’s nephew had brought out after his death. But instead, Soemmerring decided on a pictorial supplement, of ‘exactly the same size and the same format’, showing growth and development step-by-step in the first five months.

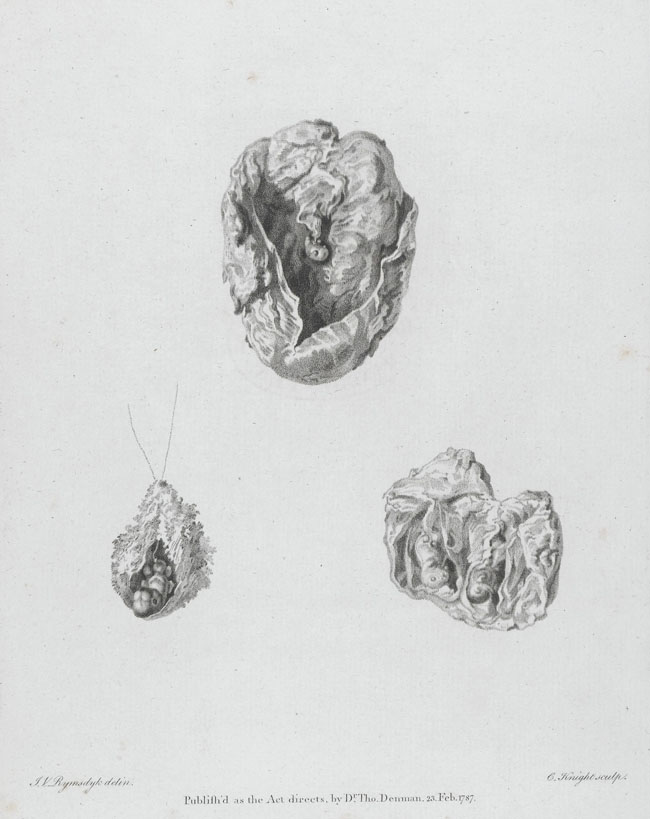

Thomas Denman’s illustrations of generation, 1787 |

The title-page of Soemmerring’s Images of human embryos, 1799 |