The sacred pregnancy. The most frequent representations of pregnancy in medieval and early-modern Christian art show the expectant Virgin Mary. Jesus, a child, is depicted inside her transparent belly or, in sculptures, within a niche closed by glass doors. In images of Mary’s visit to the heavily pregnant Saint Elizabeth, the little Jesus and John the Baptist rejoice in their mothers’ tummies. The cult of the pregnant Virgin, or ‘Virgin of the Expectation’, flourished through the late Middle Ages. But the Council of Trent (1545–63), reforming the Catholic Church in response to the Protestant Reformation, imposed a uniform orthodoxy that attacked such images as indecent.

While images from the early 1800s strike expert modern eyes as merely abnormal, pictures and models from previous centuries are very strange indeed.

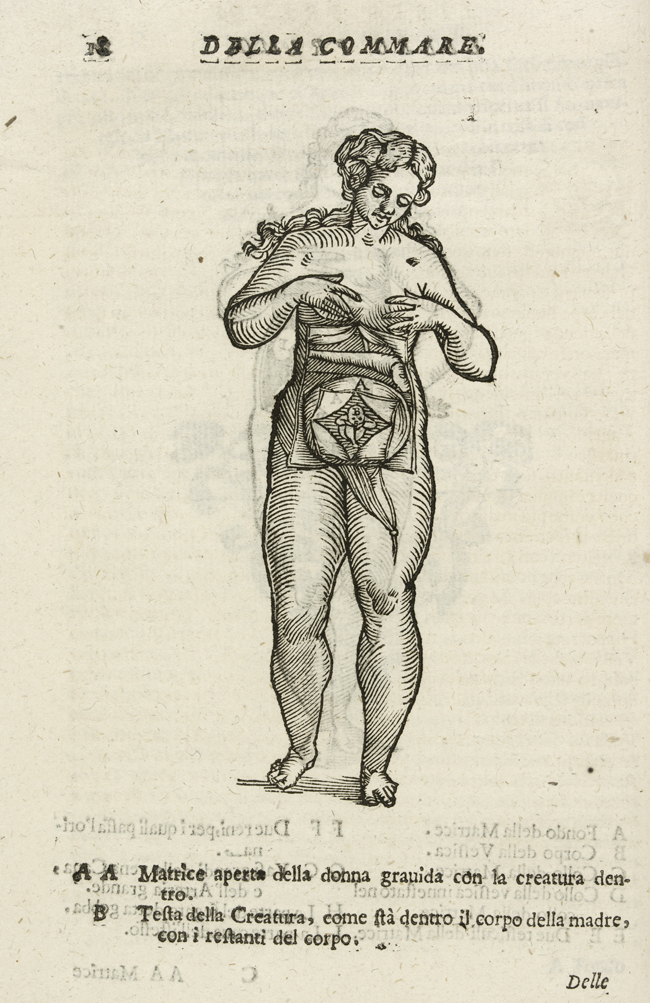

Representations from the later medieval and early-modern periods—roughly 1300 to 1750—show not a developing embryo, but other members of the diverse family of ‘the unborn’: Christ safely sheltered in the Virgin Mary’s womb, the coming child trying out different birth positions and a tiny homunculus contained in the head of a sperm. The images are so diverse because pregnancy and generation had such various meanings: the acquisition of an immortal soul, the making of family ties and the organization of unformed matter.

The contents of the womb were mysterious to medical men and to women. From the Middle Ages on, anatomists depicted adult bodies ever more realistically, but representations of the unborn remained largely schematic. Bodily sensations might convince women they were pregnant, but the existence of a child was hidden from the world and for the most part uncertain until birth.