Medical views

Physicians and surgeons were deeply interested in the contents of the womb, but had limited access to pregnant women’s bodies. The rich medical representations of the unborn remained largely emblematic.

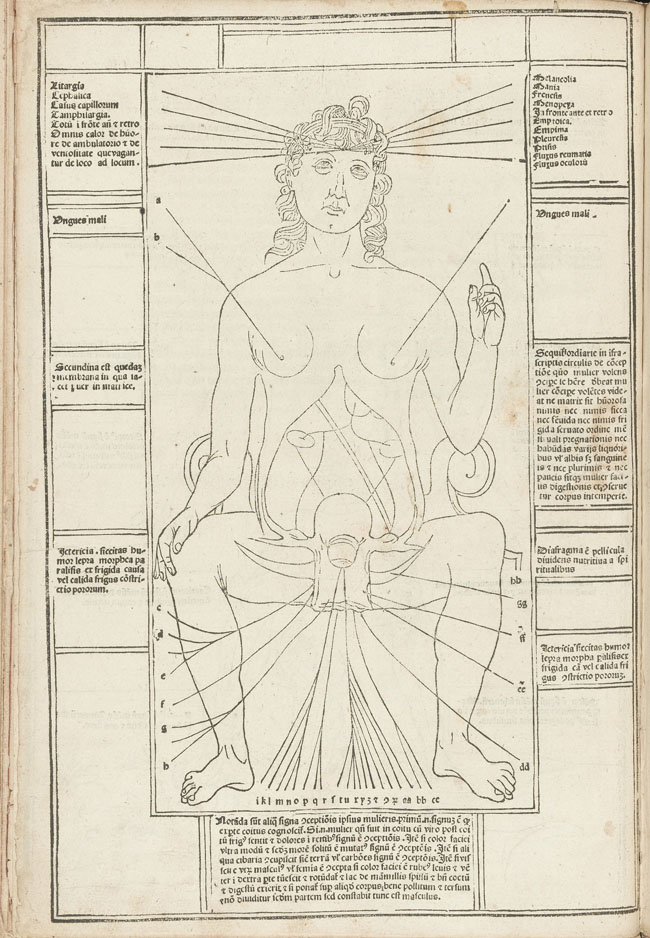

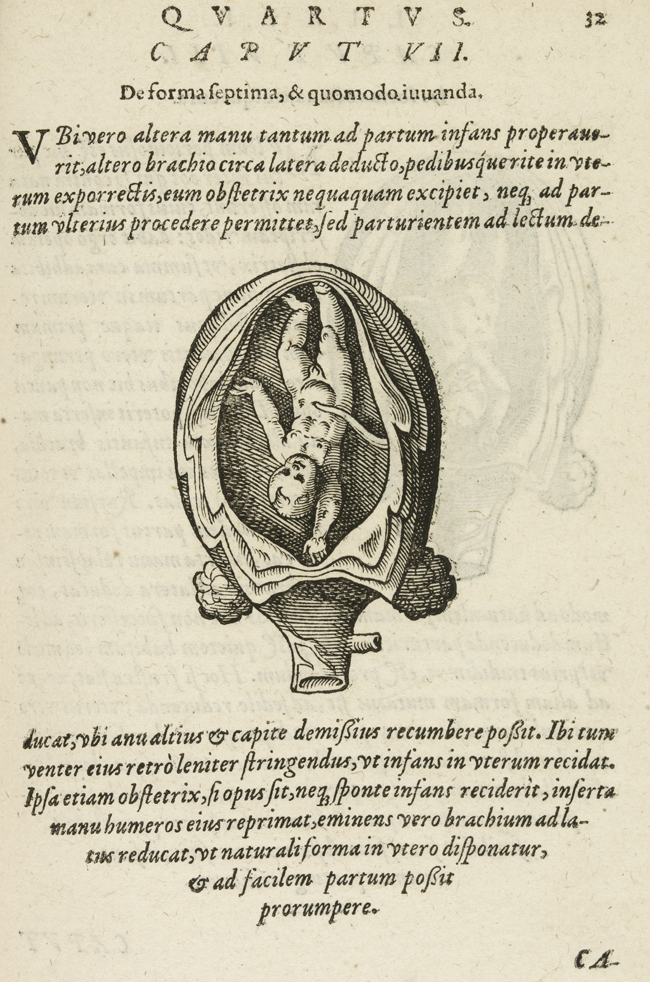

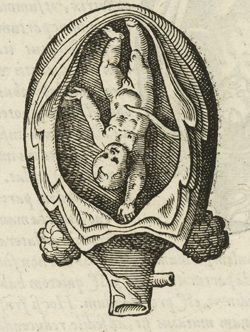

Medical interest in the womb arose from major concerns in medieval societies. Family ties and the birth of heirs decided the destinies of dynasties and states. Medico-legal experts confirmed impotence and sterility in cases of marriage annulment and freed pregnant women from torture and corporal punishment. When inheritance was disputed, they established parentage from physical resemblance and the duration of pregnancy. The womb and its contents were pictured widely in medical literature, but these images were not realistic. Midwifery textbooks contained standardized representations of positions and presentations in labour, while anatomical treatises showed symbols of children to come.

Yet it was not only children that grew in the womb. If misdirected, the generative force could instead produce malformed or unformed mola: a ‘false fruit’. Early miscarriages and abortions, brought to physicians by midwives or the women concerned, may have diverged too far from an adult-based ideal of perfection to be recognized as normal. Only around the end of the eighteenth century would these be reclassified as embryos.

The uterus as the site of generation, 1495 |

About to be born, 1580 |