Experiencing pregnancy

In Europe before 1800, the womb was still culturally protected and medical predictions of pregnancy depended crucially on the testimony of the woman concerned.

Distinguished by their periodic discharge of fluids, especially blood, women in their fertile years were perched between good growth and evil stagnation. An interruption of the monthly course was variously interpreted as a harbinger of pregnancy or a sign of ill health: a woman might be expecting a child or need to take herbs to restore the flow. Something she passed could be the returned period, an abortion or a false conception.

Pregnancy remained uncertain even when the bleeding failed to reappear and the abdomen started to enlarge. The earliest reliable sign was ‘quickening’, when a mother-to-be felt the child move in the womb—but in some cases pregnancy was revealed for certain only at birth. In difficult cases wealthy women consulted male practitioners. But birth was generally a domestic and female affair, supervised by midwives, and male surgeons were called in emergencies only.

A lying-in chamber, 1580 |

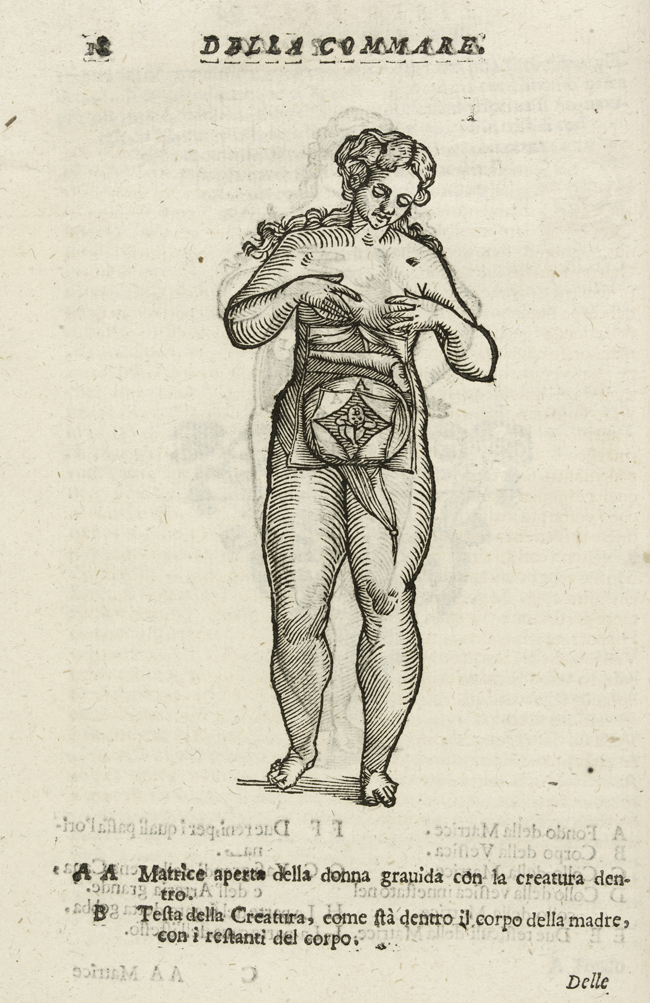

Instruction about pregnancy and childbirth, 1642 |