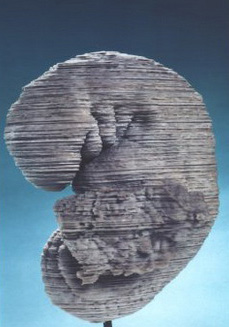

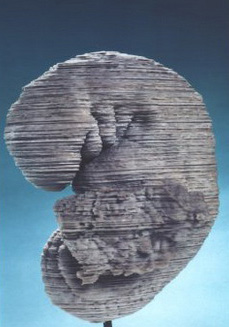

Reconstruction of embryo 836. This plaster representation of the external form was produced by Osborne Heard. A digital model of stage 13 was used as the prototype for the Visible Embryo Project that started in 1993. Animation may be seen here .

31.75 x 15.24 x 12.7 cm. National Museum of Health and Medicine, Washington, D.C.

A biography of an embryo. In early 1914 Johns Hopkins gynæcologist William W. Russell removed the uterus from a 25-year-old patient, Mrs R, who was suffering from a fibroid tumour. At the Carnegie Department, the embryologist Herbert M. Evans found in the uterus a perfect specimen estimated at about 28 days (later re-classified as 32). The embryo, catalogued as number 836, came to designate Streeter’s horizon XIII and O’Rahilly’s stage 13, distinguished by the appearance of limb buds, closed neuropores and the division of the heart into primordial atrium and ventricle. The embryo was photographed, drawn and used to produce models, at least one of which was lost during the collection’s difficult times in the 1960s. But in the 1990s, embryo 836 became the prototype for the NIH-funded ‘Visible Embryo Project’. This digitalized sections and then put them together into dynamic virtual 3-D animations. Embryos dead for decades thus came to communicate ‘life’.

From horizons to stages

The Carnegie collection was used to produce stages that remain the authoritative standards of human development.

Normal plates could not easily accommodate new specimens, which might be more advanced in one respect but delayed in another. So in 1914 Mall classified photographs of the external forms of 266 human embryos from 2 to 25 millimetres long into 14 formal stages, each with characteristic anatomical features. He lacked early specimens, but by the time his successor George L. Streeter retired in 1940 the collection had grown considerably. From internal and external features Streeter now constructed 23 divisions for the first seven weeks.

Wary of the precision that the term ‘stage’ implied, Streeter borrowed ‘horizons’ from geology and archæology to indicate a flexible system based on multiple morphological criteria. Streeter’s articles brought together line drawings, photographs of specimens and reconstructions, descriptions of Carnegie embryos and a reference guide to specimens in other laboratories—but only for horizons 10–23. In the early 1970s, Ronan O’Rahilly, who curated the collection, extended the project to the beginning of development, revised the other horizons and renamed them stages.

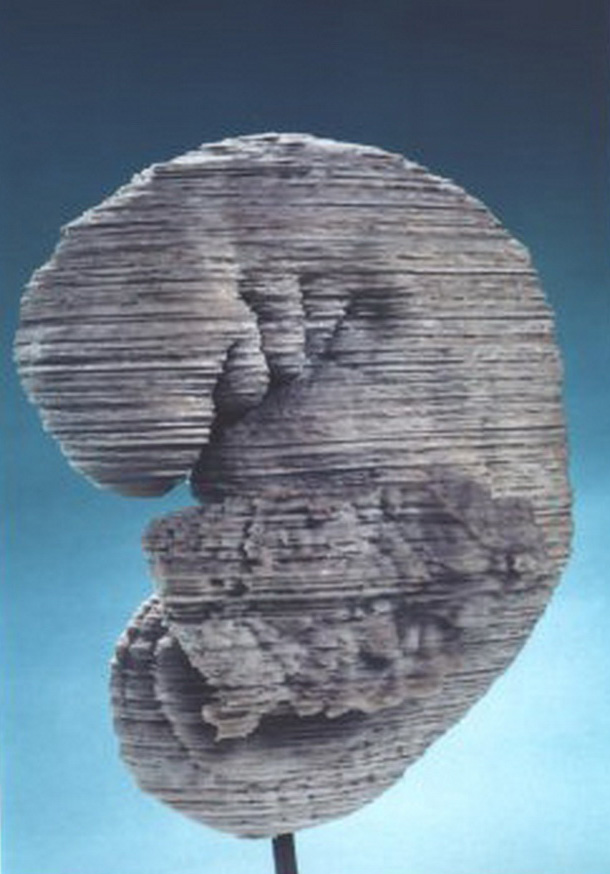

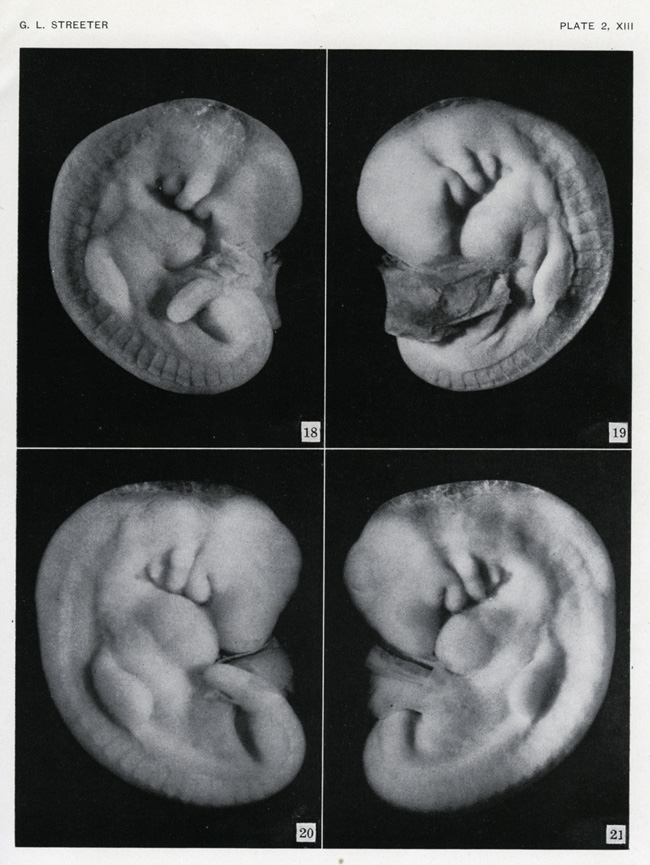

Streeter’s horizon XIII. This was based on 26 embryos collected between 1897 and 1943.

The definitive arm-bud ridge and a recognizable leg bud defined the group. The blood circulation is well established and

the heart chambers distended. Certain areas of gut epithelium are definitively allotted to the lung, pancreas and liver.

The ovulation age of the group was estimated at 28±1 days and the length of the embryos was in most cases between 4 and 5 mm.

Figures 18 and 19 show embryo 7889, a younger member of the horizon XIII group. It is coiled more closely and measures 4.2 mm.

Figures 20 and 21 show the older embryo 7618, whose arm buds are more developed. Both embryos were collected from women

whose uteri had been removed at the Free Hospital for Women in Boston, in 1939 (7618) a

nd 1941 (7889).

Photographs (x 20 magnification) by C. F. Reather from George L. Streeter, Developmental horizons in human embryos: age groups XI to XIII. Collected papers from the Contributions to Embryology, Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1951, plate 2, horizon XIII.

Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Streeter’s horizon XIII, 1951

| |

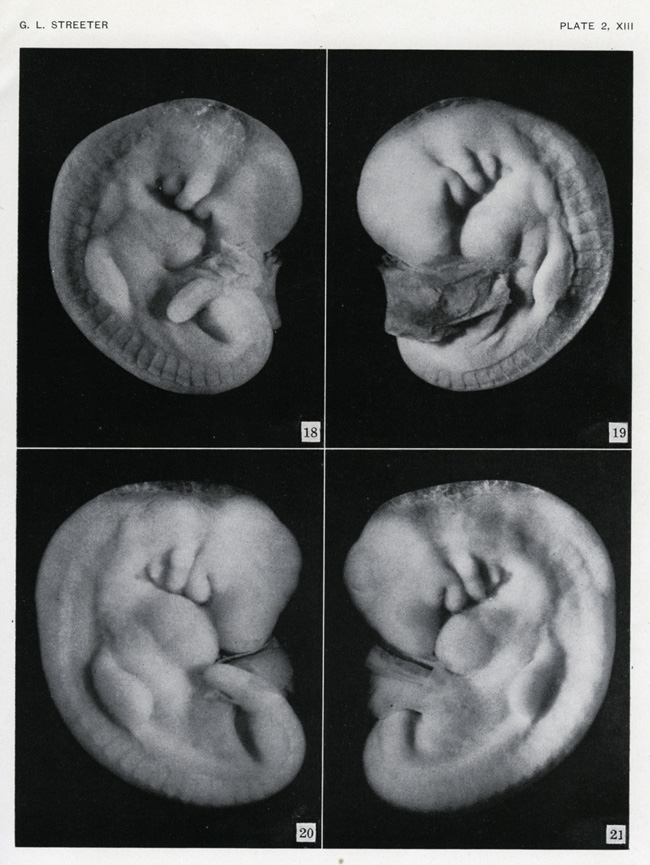

Working with models and photographs. In this photograph, three people—‘Frank K.?’,

the Swedish researcher Bent Böving (middle) and Ellen Monaghan (right)—are shown examining some of Heard’s reconstructions

and consulting what is surely Streeter’s Developmental horizons. The model on the right could be horizon XIII but

the stage they are consulting in the book appears later, possibly XVII (plate 2). The cabinet behind contains reconstructions

and, on the top row, what may be specimens in jars.

Undated, c.1970s.

Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Working with models and photographs, ?1970s

|