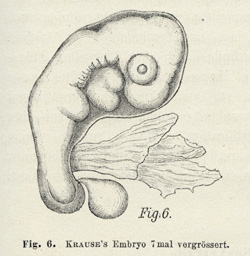

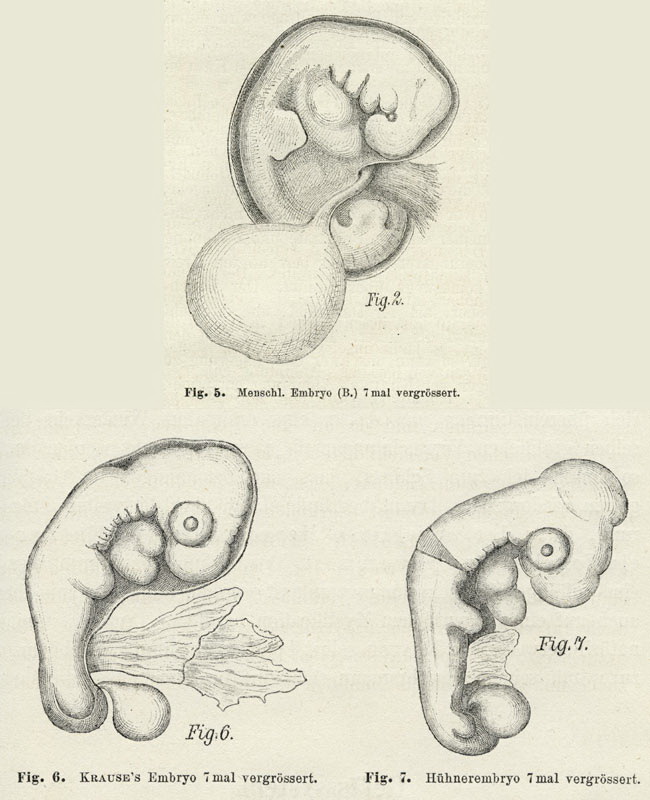

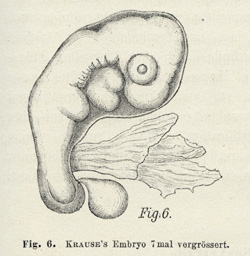

Comparing chick and human embryos.

Drawings by Wilhelm His comparing his human embryo (fig. 5),

Krause’s embryo (fig. 6), and a chick embryo (fig. 7). The disputed

part was the allantois, a structure known in birds and some

mammals to form a bridge between the embryo proper and the chorion

that was crucial to embryonic nutrition. Krause’s embryo featured

what he claimed was a prominent free allantois (the vesicle

near the posterior end), but His argued that in humans the allantois

was never visible in this form and reinterpreted the specimen

as that of bird. Either a bottle had been mislabelled or Krause

had been deceived.

Wood-engravings from Wilhelm His, Anatomie menschlicher

Embryonen, part 1: Embryonen des ersten Monates,

Leipzig: Vogel, 1880, figs 5–7, pp. 70–1. Drawing of Embryo

B 6.6 cm tall.

Excluding an embryo. The story of the

embryo it took His most effort to exclude shows how open human embryology

still was when he began work. In 1875 an anatomy professor, Wilhelm Krause,

had described a human embryo as supporting Haeckel against His. For five

years embryologists debated the possibility that the embryo was abnormal,

but in 1879 His announced that it was not human at all, but a chick. Even

then, Krause fought on and others continued to offer alternative explanations.

The matter was decided only in 1882, when anatomists gathered to view the

famous object. They declared it a bird, but that it was a chick they could

not say; it might just as well have been a duck, a goose—or a turkey.

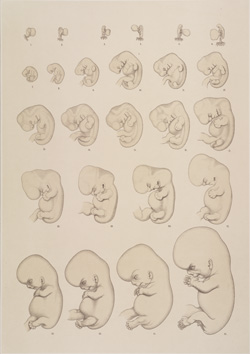

Setting standards

Wilhelm His invented a new kind of visual standard, a ‘normal plate’.

His arranged specimens in developmental order and selected appropriate

representatives. This was far from trivial. He could not simply sort

the embryos by time from fertilization, since this was not reliably known,

so instead set up a special measure of length. For the variously shaped

earliest specimens, he fell back on his judgement of overall form. Selecting

normal specimens from material that, by its very origin in abortions, was

suspected of abnormality was even harder. His could only compare his own

and published descriptions among themselves as he

drew and redrew, excluding venerable

specimens and some undistinguished recent offerings from gynęcologists.

Though His began by setting up ‘stages’ of human development, he soon

abandoned this system in favour of a series of ‘norms’. These were not,

as for Soemmerring, the most perfect, but merely

individuals he took to be characteristic, well preserved and well described.

So though His faced fundamentally the same problems, he solved them in significantly

differently ways. He called the resulting seriation a Normentafel

or ‘normal plate’.

A drawing apparatus or ‘embryograph’. For His,

exact drawings of whole embryos and sections were the

foundation of all serious work. Committed to mechanical

drawing aids, he found the standard combination of microscope

and camera lucida unsuitable for the low magnifications

(5–20 x) that embryological specimens required. So he

replaced the microscope with lenses freely movable on

a graduated retort stand. From the early 1880s Edmund

Hartnack of Paris and Potsdam sold the apparatus as

an ‘embryograph’. We see a drawing prism (top), objective

lens, stage and mirror (bottom); the image was projected

onto a drawing table. The embryograph was widely used,

but Haeckel, defending himself against

accusations of tendentious drawing,

mocked His for reducing the morphologist to an automaton-like

‘embryographer’.

Embryograph, total height of c.45 cm, acquired

from a Dr M. Abraham in 1942.

Historical Collections, National Museum of Health

and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington

D.C.

A drawing apparatus or ‘embryograph’,

late 1800s

|

|

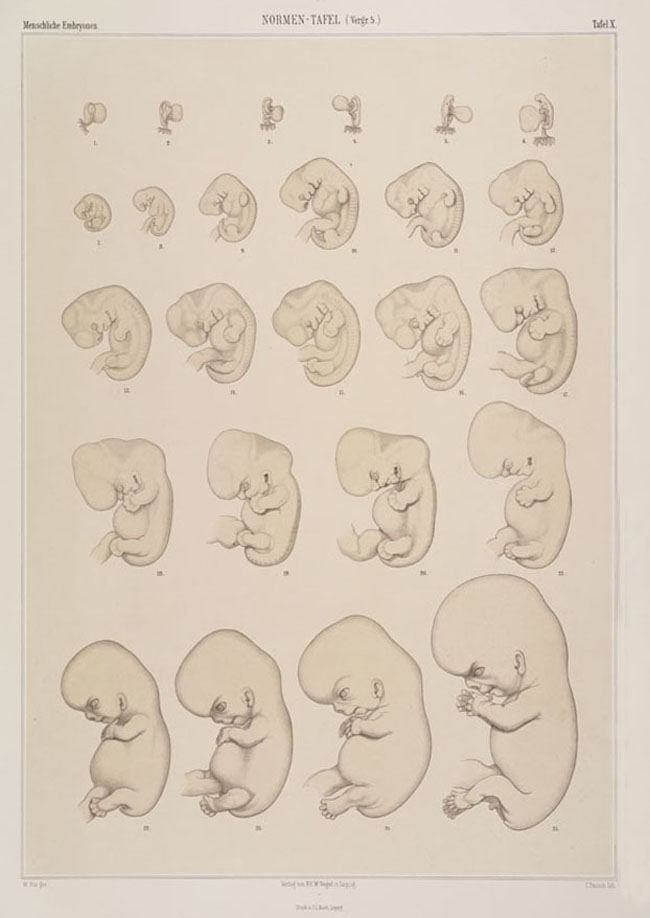

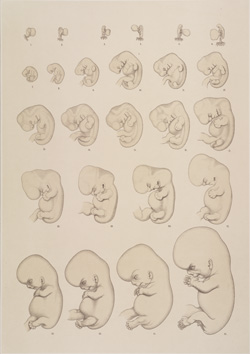

Normal plate by Wilhelm His. His had his artist

draw embryos from about the end of the second week to

the end of the second month. The plate almost creates

the impression of a single embryo at a succession of

stages, but in fact brought together specimens from

diverse medical encounters. The ninth figure shows

embryo A.

Lithograph by C. Pausch from Wilhelm His, Anatomie

menschlicher Embryonen, part 3: Zur Geschichte

der Organe, Leipzig: Vogel, 1885, plate X. Border

46 x 33 cm.

By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University

Library.

Normal plate by Wilhelm His, 1885

|